One of the prevailing forms of communication in modern microservice architectures is asynchronous messaging. This is the backbone of the event-driven architecture model. In this model, services send messages to a message broker, which then distributes (publishes) the messages to interested (subscribed) clients. A message can be used to describe an event in the system, such as the creation or update of an entity. This allows you to loosely couple different components of your system by having them publish or subscribe to events that they care about.

But what happens if there is a subscriber that wants to react to a group of events as an aggregate? In other words, what

if you wanted to do something only after all the update events stop being published, rather than reacting to each and

every one as they come in?

Let’s look at a concrete example.

Aggregating Social Media Metrics

Let’s say you are building a system that collects metrics on your social media posts. Your system needs to provide both an individual

view of post performance and view of posts’ performance as a whole. Let’s call metrics on individual posts post-level metrics

and metrics on your posts as a whole account-level metrics. To keep things simple, let’s assume all post-level metrics can

be aggregated using a sum:

$M_{account} = \sum_{i=0}^{N_{posts}} M_{post_{i}}$

From the equation above, it is clear that account-level metrics depend on the post-level metrics. Every time a metric on a post changes, we will

need to recompute this sum[1]. In an event-driven architecture, you may have a service that performs this aggregation by

listening to post-metric-updated events. If many of these events are produced within a short period of time, the service

will be computing this sum many times over, with only the last computation being valuable (all other computations would produce

a stale value). What we would really like to do in this situation is detect when the last post-metric-updated event comes

in and only then compute the sum. But how do we know which event is the last?

Determining which event is last is actually a difficult problem and can’t be solved in a general context. The concept of “last” is application specific. In our example, a post can have it’s metrics updated at any time. If we are okay with some degree of staleness to our account metrics, we can implement a delayed computation that occurs only after we stop receiving events for a certain amount of time.

The Ideal Event

Ideally, what we would like to have is to have a slightly different event than our post-metric-updated event. What we really

want is a post-metric-last-updated-X-minutes-ago event, where X is some acceptable delay. If each post-metric-updated

event contains a list of all the updated metrics, then the post-metric-last-updated-X-minutes-ago event should contain

the superset of all the metrics that were updated. Let’s define the time duration, X, the folding window because it is

the minimum duration of time at which similar events will be folded into a single event.

But how do we produce such an event?

We will need some code that will do the following for each account:

- Listen for

post-metric-updatedevents - Keep a super-set of all the updated metrics in the events

- Keep track of the last time a

post-metric-updatedevent comes in - Produce a

post-metric-last-updated-X-minutes-agowhen we don’t receive an event forXminutes

This turns out to be fairly simple to implement with the use of Redis sorted-sets.

Sorted Set

A sorted set is a unique collection of strings that have an associated score. The score is used to sort the entries

within the set.

For example, a sorted set would be a perfect data structure for storing a user scoreboard:

| Rank | Name | Highscore |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sharon | 1050 |

| 2 | Abdul | 800 |

| 3 | Calvin | 780 |

| 4 | Pirakalan | 660 |

| 5 | Nirav | 600 |

We can insert the data above into the sorted set in any order and it will maintain the entries in the order of high-score.

>> ZADD highscores 780 Calvin

>> (integer) 1

>> ZADD highscores 1050 Sharon

>> (integer) 1

>> ZADD highscores 660 Pirakalan

>> (integer) 1

>> ZADD highscores 600 Nirav

>> (integer) 1

>> ZADD highscores 800 Abdul

>> (integer) 1

It is then very simple to ask the sorted set for the top N results with ZREVRANGE.

(You could also get the results sorted by ascending order by using ZRANGE)

>> ZREVRANGE highscores 0 5 WITHSCORES

1) "Sharon"

2) 1050

3) "Abdul"

4) 800

5) "Calvin"

6) 780

7) "Pirakalan"

8) 660

9) "Nirav"

10) 600

Or get values within a range of scores with ZRANGEBYSCORE.

>> ZRANGEBYSCORE highscores 700 800 WITHSCORES

1) "Abdul"

2) 800

3) "Calvin"

4) 780

And of course you can delete keys from the sorted-set with ZREM.

>> ZREM highscores Abdul

(integer) 1

Folding Events

Since the sorted set can only have unique values, we can use it to “fold” a group of events into a single event.

In order to do that, we need to remove unique information from the events such that they serialize to the

same string value. We can use the time of the event as the score in the sorted-set. Each time an event is added, we update

the score, thus keeping track of the last event in the group. Our sorted-set then holds a time-ordered collection

of events, where each element represents a folded view of events from each group. We can then regularly query the

sorted-set with ZRANGEBYSCORE to get values with timestamps (scores) before time.Now()-X.

These values are then published as post-metric-last-updated-X-minutes-ago events and removed from the sorted set[2].

Back to our example, the post-metric-updated event has the following schema:

// PostMetricUpdatedEvent is published when metrics change on a post. It contains the changed metric values.

type PostMetricUpdatedEvent struct {

PostID string `json:"id"`

AccountID string `json:"account_id"`

UpdatedMetrics map[string]float64 `json:"metrics"`

}

And we have the following events being published, shown below in their JSON serialized form:

{"id": "post_1", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"likes": 10, "shares": 5}}

{"id": "post_2", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"comments": 25, "impressions": 16}}

{"id": "post_3", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"likes": 5, "shares": 2}}

{"id": "post_4", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"comments": 33, "impressions": 8}}

{"id": "post_5", "account_id": "account_2", "metrics": {"likes": 12, "shares": 15}}

{"id": "post_6", "account_id": "account_2", "metrics": {"likes": 3, "shares": 1}}

These 6 events span two unique accounts (account_1 and account_2) and should therefore ideally create two separate

post-metric-last-updated-X-minutes-ago events. Remember, a sorted set stores unique strings, so we cannot just

insert these JSON strings into the sorted-set as is. If we did, they would be stored as 6 different entries in the set.

We need to identify the group key for all the events that we want to fold.

The group key should remove all uniquely identifying information in the event such that events within the same group have the same

serialized value. In our example, the group key would be just the account_id field, since we just want one event per account:

{"account_id": "account_1"}

{"account_id": "account_2"}

But wait… We just lost a bunch of information from our events! That’s right. I never said this folding was lossless! In some cases this may be acceptable, you may be able to gather that information elsewhere, say from an API call, or it may not be relevant for what you are trying to do on the subscriber side.

In cases where you do need that information, we can store it separately in a database as we are inserting values into the sorted-set. When querying the sorted-set for events to publish, we can “unfold” the event by enriching it with the information we stored in the database.

In our example, we need a list of metrics that have changed so that we know which metrics to aggregate.

We can easily keep track of these metrics in a regular Redis set. When we query the sorted-set to get

the folded event older than X, we also grab the metrics that have changed from the regular set. We can then assemble

the post-metric-last-updated-X-minutes-ago event:

type PostMetricUpdatedEvent struct {

AccountID string `json:"account_id"`

UpdatedMetrics []string `json:"metrics"`

}

which in our example looks like:

{"account_id": "account_1", "metrics": ["likes", "shares", "comments", "impressions"]}

{"account_id": "account_2", "metrics": ["likes", "shares"]}

The service performing the aggregation can then subscribe to these events and be notified only once metrics have stopped

being updated. We can rest assured that we will compute the value at most once in the X minutes since the

last time a post metric was updated.

Folding Ratio

To get a feel for how long we should set our folding window to be, we can calculate the folding ratio, ${F}_{R}$:

${F}_{R}=\frac{N_F}{N_E}$

where $N_E$ = Number of fold-eligible events and $N_F$ = Number of actually folded events.

When inserting into a Redis sorted-set with the ZADD operator, Redis will tell you how many new elements were added to

the sorted-set (score updates excluded). Assuming we are inserting one event at a time, the number of folded events is

measured by how many times the ZADD operation returns 0 and the number of new events is measured by how many times

ZADD returns 1. With this in mind, we can measure the following values:

$N_E= N_{Total} - Count(ZADD == 1)$

$N_F$ = Count(ZADD == 0)

$F_R = \frac{Count(ZADD == 0)}{N_{Total} - Count(ZADD == 1)}$

where $N_{Total}$ is the total number of events.

But there is a caveat; we are also popping elements off of the sorted set in order to publish the folded event.

If the folding window is too short for the timing of our incoming events, we are going to be removing an element

from the sorted set just before adding a new event that would have otherwise been folded.

In this situation, we will be over measuring our number of new events and under measuring the number of folded events.

Another way to look at this is that the value of ZADD only acts as a proxy for the folded count from Redis’ perspective.

Below is an example of what that could look like:

{"id": "post_1", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"likes": 10, "shares": 5}} -> ZADD Returns 1 (new)

{"id": "post_2", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"likes": 25, "shares": 16}} -> ZADD Returns 0 (folded)

{"id": "post_3", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"likes": 5, "shares": 2}} -> ZADD Returns 0 (folded)

Publish folded event {"account_id": "account_1"}

{"id": "post_4", "account_id": "account_1", "metrics": {"likes": 33, "shares": 8}} -> ZADD Returns 1 (fake new)

{"id": "post_5", "account_id": "account_2", "metrics": {"likes": 12, "shares": 15}} -> ZADD Returns 0 (new)

Publish folded event {"account_id": "account_2"}

{"id": "post_6", "account_id": "account_2", "metrics": {"likes": 3, "shares": 1}} -> ZADD Returns 1 (fake new)

If your system is processing a large number of folded events ($N_{Total} \gg Count(ZADD == 1)$) and your folding window is reasonable[3], then the error becomes negligible and the folding ratio simplifies further:

${F}_{R}\approx\frac{Count(ZADD == 0)}{N_{Total}}$

If it is really important that you have the most optimal folding ratio, you will need to do some offline analysis such as looking at historical events within a time range. In this case, you will actually know the number of events that should be folded. In most cases, the timing of your events will be irregularly spaced and you will never consistently achieve 100% folding. Even then, any non-zero folding is still cutting the amount of work your system is doing.

The example we have been using throughout this article is a real world scenario. In production we see anywhere between 85% and 98% folding over hundreds of thousands of events per day. Without event folding, we would have overloaded our database a long time ago and be forced to drop our event-driven approach in favour of something more traditional such as scheduled cron jobs.

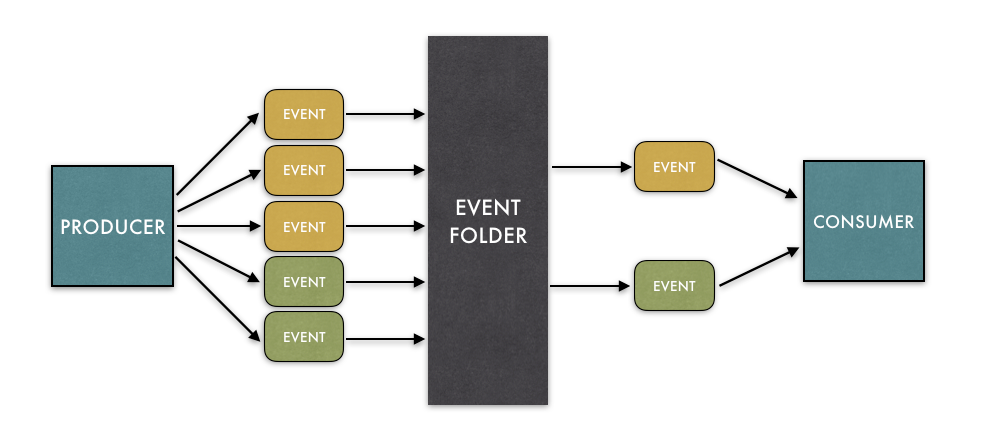

Placement of the Event Folder

The event folder can be placed on either the publisher side or on the consumer side. Where you decide to place the event folder ultimately comes down to how many consumers want folded events. By folding on the publisher side, you can reduce complexity for consumers downstream. However, if only one consumer cares about folding events, it may be cleaner to place the event folder on the consumer side and not have to make any changes at the producer. If you place the event folder on the publisher side, there is nothing wrong with publishing both folded and unfolded events, just be sure to place them on separate topics to prevent confusion.

Another Use-case: Database Syncing

Another use-case where the event folder is highly effective is during database syncing. In a CQRS pattern, we can separate database technologies used for writing and reading by syncing all writes to the read database. Some databases such as ElasticSearch perform poorly for document updates[4]. Using an event folder we can reduce the number of writes to ElasticSearch, significantly reducing the number of deleted documents that need to be garbage collected.

A Powerful Tool

The event folder can be a powerful tool in your system’s architecture. It can be the difference in an event driven system’s viability. The event folder I have outlined in this article is designed around transient spikes in events. If your events are not transient, you may find that your folded events may never be published due to a constantly resetting folding window. With a few adjustments, this design can be used for non-transient event streams as well.

Appendix

[1] Many social networks provide APIs for gathering account level metrics so you don’t need to do this aggregation yourself. However, there are certain metrics which are not supported and cause us to have to do the aggregation ourselves.

[2] While Redis sorted-sets do have the ability to atomically pop elements from the top or bottom of the sorted set, it

unfortunately does not have an atomic way to query and remove elements from the middle. This means that we have to make

two separate commands: ZRANGE to get the values and ZREM to remove the key after we publish the event.

The consequence of this is that there is are race conditions if you have multiple threads looking for folded events

to publish. This means a folded event can be published more than once. If this is a real issue you can consider using

global locks or partitioning the key-space, with the trade-off of added complexity.

[3] You should have some reasonable initial guess for your folding window. If not, take a sampling of events and determine it retrospectively offline. If your latency requirements allow for it, start with a larger folding window and gradually reduce it while monitoring your folding ratio.

[4] Even though ElasticSearch has APIs for updating documents, under the hood it is actually indexing a new document and marking the old document for deletion.